PRESENTED BY

THE DOMESDAY BOOK OF DOGS

Girt Dog of Ennerdale.

For a few months in 1810 at Ennerdale in the Lake District the locals were at their wits' end as the vale was ravaged by a devil dog. By the end of the long, protracted incident they had lost an estimated three hundred sheep.

Known by various synonyms: the Vampire Dog of Ennerdale; the Beast of Ennerdale; the wild dog of Ennerdale, whatever was killing sheep supposedly did so in a quite macabre manner. Whereas parts of the cadavers may have been eaten some sheep were found with chunks of flesh missing and yet still alive, but many victims were discovered drained of blood either with or without internal organs.

Literally reams have been written about the depredations of the Girt Dog (Great Dog) but three questions have come down to us over the years:

What was it?

Where did it come from?

What happened to it after it was shot, stuffed and mounted?

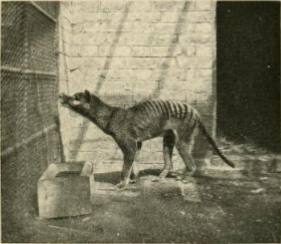

Originally it was thought that the Girt dog could have been a greyhound mastiff crossbreed but in the last few decades or so two other candidates have been suggested: the thylacine, Freeman 2000; Emily rothery, 2015 (amongst others) and the striped hyena. The beast weighed 8 stone (1 CWT). This figure seems a little on the heavy side for the two alternatives to the mastiff cross.

Both thylacines and hyenas have a distinctive smell; thylacines in Tasmania were sometimes referred to as 'hyenas' because of their smell. No witnesses mentioned a smell, but this could explain the hesitancy of some hounds once they realised what they'd been called on to hunt. Striped hyenas are usually carrion eaters, they certainly don't suck blood. Tales of vampirism involving the thylacine were put to rest by Paddle, 2001. In the last few years of the thylacines existence, up to 1936, there were claims that thylacines were killing sheep and sucking there blood. At the same time the possible effects of an enormous number of feral dogs was ignored by the Tasmanian authorities. As Paddle points out vampirism was used as an excuse to drive the Falklands Islands Wolf into extinction in the late nineteenth century.

In March 1785 a mastiff was shot in Northumberland after a three months reign of terror and, according to Bewick, 1792, "when he caught a sheep, he bit a hole in its right side, and after eating the tallow about the kidneys, left it: several of them, thus lacerated, were found alive by the shepherds; and being taken proper care of, some of them recovered, and afterwards had lambs". This story of finicky eating predates the beast of Ennerdale by twenty-five years.

It was claimed that the Girt Dog was known to flee, initially, before hounds and then to wait 'til the leading hound had caught up before giving it a savage bite across the foreleg: hyenas will attempt to bite dogs' legs. The modus operandi of the Northumberland mastiff, however, was different and more dog-like, if the hounds caught up with him he'd simply lie on his back and proffer his underbelly and the pursuing dogs immediately called off the chase. The mastiff would hang around, getting his breath back, 'til the huntsmen caught up with the hounds and he'd be off again and the hounds wouldn't follow until they were instructed by the huntsmen. It's unlikely that the thylacine's famous 'shambling canter' could afford the hunters the marathon chases described in the tales.

One enterprising hunter staked out a bitch in heat and hid nearby with a gun. The beast apparently showed some interest but stayed warily out of range. Thylacines avoided dogs if they could, whereas a hyena might regard a tethered sheepdog as food.

People at the time would have been aware of exotic animals thanks to the travelling menageries that started trading in the eighteenth century. Unfortunately the names given to the animals on display were none too accurate. The spotted hyena, the thylacine and sometimes the striped hyena too were dubbed 'tiger wolf' (Frost, 1874) - this is a flyer from Atkins's Royal Menagerie. Wombwell's Menagerie has been suggested as the source of the likely escapee but 1810 is a little early for Wombwell's. No humans were ever attacked, yet hyenas, though carrion eaters, are opportunistic and would probably take a child. Judging by the Girt Dog's cunning, stamina and running ability it's probably safe to assume the mastiff crossbreed hypothesis is correct. Particularly since one witness observed it cocking a leg. Not a brindled dog, nobody's confused by brindling, but possibly streaked across the flanks as occasionally occurs in greyhound colouration.

There is one major difference between the thylacine and canis that appears to have been missed amidst all the hypothesising; the genitalia are markedly different. Marsupial genitals are the opposite way around compared to placental mammals with the testes being placed 'above' the penis, i.e. further away from the tail. As the Girt dog was paraded around the local pubs after its demise you'd expect people to notice if things were topsy-turvy in the groin area. Particularly as some people must have checked whether the culprit had been a dog or a bitch. Male thylacines also had a rudimentary, rear-facing, pouch.

Dickinson, 1875, in his most excellent, in-depth, blow by blow account of the whole incident reckoned that the stuffed remains found their way to Hutton's Museum, Keswick. The museum shut down in the 1840s and Atkinson 1906 claimed in verse form (2nd verse, page 59) that the small boys of the town smashed up the exhibit.

We got off lightly in a way compared to the French: the Beast(s) of Gevaudan killed and partially ate hundreds of rural inhabitants, not sheep; and Courtauld and his pack exterminated dozens of Parisians.

|

| Thylacine. Grenshaw 1905. |

Thomas Bewick. 1792. P305

Thomas Frost. 1874

Cumbriana; or, Fragments of Cumbrian Life

William Dickinson. 1875. PP178-190

More natural history essays. Graham Renshaw.

London, Sherratt & Hughes. 1905

Frederic Atkinson. 1906. PP53-59

Rechard Freeman, 2000

Bob Paddle. 2001.

Emily Rothery. 2015.

Amy Spurling. E&T. 2018.

Slight possibility of thylacine survival in the wild.

De-extinction of the thylacine from dunart host. Via Newsweek.

University of Melbourne version. Via 9News

Is the Tasmanian tiger extinct? A biological-economic de-evaluation.

Comments

Post a Comment